Oscar Odena explores the use of music education as a tool for social inclusion.

The power of music to affect human beings is well documented in the literature. Marketing and psychotherapy scholars have shown how music is used to alter the consumer’s mood (Brown & Volgsten, 2006) and to develop communication skills with children on the autistic spectrum (Bunt, 2012). Likewise, educational researchers have suggested that music education activities can be used for purposes other than music, such as developing inclusion in schools and communities.

In Northern Ireland, cross-community music education activities are allowing students from both main communities to work together. In my recent exploratory study of using music education as a tool for inclusion in Northern Ireland it was evidenced that activities such as youth orchestras and primary school music projects across schools were allowing collaborative work between students from previously conflicted communities (Odena, 2010 and 2014). And in a number of countries, orchestra programmes inspired by El Sistema – Venezuela’s National System of Youth and Children’s Orchestras and Choirs – appear to re-engage and raise children’s aspirations in disadvantaged neighbourhoods (Creech et al, 2014).

A core aim of these orchestra programmes is ‘to effect social change through the provision of musical opportunities for young people from communities who would not otherwise access such experiences’, with the premise ‘that social transformation can be brought about through intensive music education’ (Creech et al, 2014, pp. 78-81).

In Scotland one such programme, Big Noise, is being evaluated with a focus not just on the benefits for participants, but also on its impact at community and societal levels, with an analysis of costs and returns on investment (Harkins, 2014). These programmes have generated interest in the transformative potential of music education, and stimulated debate about effective practice. For instance, there is interest in the preferred frequency for contact time, how to overcome physical barriers, and how to implement non-selective admission and continuity based on commitment rather than achievement.

Different countries take different approaches to using music as a tool for inclusion. One important practical implication from the literature is that new initiatives would need to focus on disadvantaged contexts and on younger people, which appears to maximise their impact.

However a number of issues remain and would merit further research. What are the effects of such educational activities on the children’s later development of identity and civic values? To what extent does music education bring about positive change, or perhaps act as a ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’? And how transferable are these activities across different countries, regions and contexts? To study these questions, longitudinal and comparative enquiries are needed that engage all actors involved, including the children. In a globalised society experiencing increased inequalities, there remains much research to be done if we are to promote more inclusive communities and education systems.

References

Brown, S. & Volgsten, U. (Eds.) (2006). Music and manipulation: On the social uses and social control of music. Oxford, UK: Berghahn Books.

Bunt, L. (2012). ‘Music therapy: A resource for creativity, health and well-being across the lifespan’. In O. Odena (Ed.), Musical creativity: Insights from music education research (pp. 165-181). Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

Creech, A., González-Moreno, P., Lorenzino, L. & Waitman, G. (2014). ‘El Sistema and Sistema-inspired programmes: principles and practices’. In O. Odena and S. Figueiredo (Eds.), Proceedings of the 25th International Seminar of the ISME Commission on Research, João Pessoa, Brazil (pp. 77-97). Malvern, Australia: International Society for Music Education. Available Open Access at http://issuu.com/official_isme/docs/2014_11_10_isme_rc_ebook_final_pp37

Harkins, C. (2014). Evaluating Sistema Scotland. Glasgow: Glasgow Centre for Population Health.

Odena, O. (2010). Practitioners’ views on cross-community music education projects in Northern Ireland: Alienation, socio-economic factors and educational potential. British Educational Research Journal, 36(1), 83–105.

Odena, O. (2014). ‘Musical creativity as a tool for inclusion’. In E. Shiu (Ed.) Creativity research: An inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary research handbook (pp. 247-270). Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

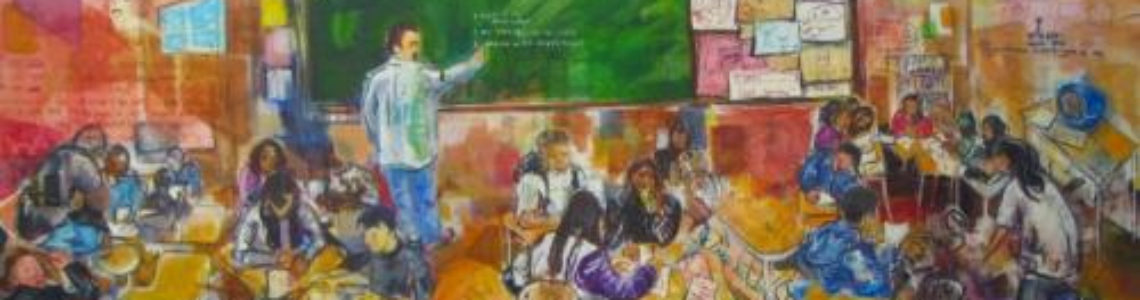

[image (c) Metro de Maracaibo]

About Oscar:

Oscar Odena is Reader in Education and a core member of the Robert Owen Centre for Educational Change at Glasgow University. Originally from Spain, he has conducted and supervised educational research in a range of contexts nationally and internationally. More information can be found on his Glasgow University webpage.