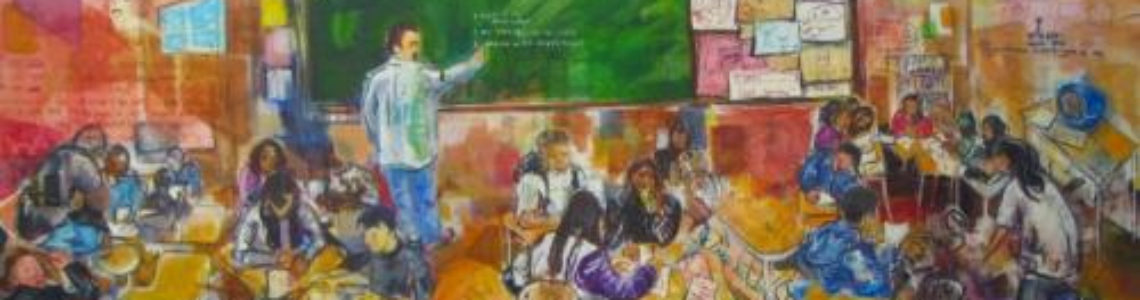

- [front image (c) Sebastien Wiertz]

By Stephen Ball

This is the name of a new report I wrote for CLASS, the Centre for Labour and Social studies, which was published in September 2013. Below is an edited extract from the report, the full version of which can be found here. Comments are welcome.

Despite the relentless and repeated criticisms of state schooling and the ongoing reform of the school system, the relationships between opportunity, achievement and social class have remained stubbornly entrenched and have been reproduced by policy. Inequalities of class and race remain stark and indeed have been increasing since 2008.

In response to this we have to reconnect education to democracy and work towards an educative relationship between schools and their communities. Put simply “we should recognize the centrality of education to larger projects of democracy and community building” (De Lissovoy, 2011). Among other things schools should have a responsibility to develop the capabilities of parents, students, teachers, and other local stakeholders; to participate, to discuss, to challenge and critique. It is time to get back to basics – to think seriously about what is the purpose of education and what it means to be educated, what schools are for, and concomitantly and crucially who should decide these things.

It is clearly necessary to dismantle systems of assessment and related incentives that encourage schools to focus their attention on some students and neglect others. Forms of assessment which rate students according to standardised age-related criteria that encourage ‘teaching to the test’ and ignore that children learn at different speeds and in different ways should be done away with. We need to engage students in discussing and designing purposeful and meaningful systems of assessment.

All of this would also mean addressing directly, and in practical ways, the complex and difficult relations between education and poverty and reworking “the tangled and confused nexus between the new realities of adolescent lives, and the out-of-touch realities of educational policy regimes” (Smyth and Wrigley, 2013: 294) in sustained and different ways. Fundamentally, this means moving away from the idea that there is a simple and inevitable relationship between social background and something called ability”. Rather than blaming teachers for low expectations or parents for lack of aspiration, we need to think about the social conditions that make effective learning possible, at home and at school. Once those conditions are met we can begin to think more about the role of expectations and aspirations.

What are needed are forms of radical incrementalism based on “consultative and participatory processes” (Fielding and Moss, 2011). This is not however a proposal for tinkering and compromise, it is a process of re-starting policy from a different set of organising principles – a staged but unequivocal abandonment of the current education policy infrastructure.

The political process of rethinking education for the 21st century, related to real social needs and economic problems, will only come about by unleashing the innovative potential of schools, teachers and communities; by building and exploiting a proper sense of “democratic fellowship” (Fielding and Moss, 2011) and by rebuilding trust in teachers and schools.

Such changes will require a new kind of teacher and a move towards forms of democratic professionalism (Sachs, 2001), with an emphasis on collaborative, cooperative action between teachers and other educational stakeholders (Thomas, 2012). Which in turn means that teachers, parents and students will have to accept challenges and demonstrate a readiness to lead and adapt. There are many risks and costs to be borne here, and there will be failures and deadends. Nevertheless the risks of not struggling against ignorance and for educational change are greater, in particular for those who bear the costs of things as they are now in education.

References

De Lissovoy, N. (2011) ‘Pedagogy in Common: Democratic education in a global era’, Educational Philosophy and Theory, 43 (10) 1119-1134. Fielding, M. and P. Moss (2011), Radical Education and the Common School, London: Routledge. Sachs, J. (2001) ‘Teacher professional identity: competing discourses, competing outcomes’, Journal of Education Policy, 16 (2) 149-61. Smyth, J. and Wrigley, T. (2013), Living on the Edge: Re-thinking Poverty, Class and Schooling, New York: Peter Lang, p. 294. Thomas, L. (2012) Re-thinking the importance of teaching: curriculum and collaboration in an era of localism, London, RSA.

About Stephen:

Stephen J Ball is Karl Mannheim Professor of Sociology of Education at the Institute of Education, University of London. He is editor of the Journal of Education Policy and has written extensively on education policy and social class. His recent publications include The Education Debate (Policy and Politics in the Twenty-first Century), How Schools do Policy, Global Education Inc: New policy networks and the neo-liberal imaginary and Education plc: Understanding Private Sector Participation in Public Sector Education.

Stephen J Ball is Karl Mannheim Professor of Sociology of Education at the Institute of Education, University of London. He is editor of the Journal of Education Policy and has written extensively on education policy and social class. His recent publications include The Education Debate (Policy and Politics in the Twenty-first Century), How Schools do Policy, Global Education Inc: New policy networks and the neo-liberal imaginary and Education plc: Understanding Private Sector Participation in Public Sector Education.

Dear Stephen Ball

Thanks you for your important article >

Regards

mahdi

Hi

I am a doctoral student in philosophy, educational equity research’m going to give you the necessary resources hog Qar.

Thanks